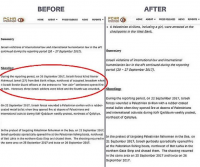

THIS week marks the 10th anniversary of the statute of the International Criminal Court. On July 17, 1998, delegates from more than 120 countries attending a conference in Rome voted to establish a permanent international criminal body to act quickly and effectively when the most serious forms of international crime were committed.

The Rome Statute confirmed the international community's aim of "putting an end to impunity". As a permanent court, the ICC is unlike previous international criminal tribunals established as ad hoc bodies, such as the Nuremberg and Tokyo tribunals following World War II and the International Criminal Tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda.

The ICC began its activities in July 2002, following ratification by the requisite 60 countries (there are now 106 state parties). Australia ratified the Rome Statute in July 2002 and remains a strong supporter of universal justice and the work of the court.

Since its establishment, the court has become increasingly active and is dealing with cases in Uganda, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sudan and the Central African Republic, with other situations also under investigation. There are four accused in detention and indictments have been issued in relation to another six alleged perpetrators. Indeed, earlier this week, the ICC's prosecutor, Luis Moreno-Ocampo, presented evidence to a pre-trial chamber of the court seeking the indictment of Sudanese President Omar Hassan al-Bashir for alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in the Darfur region. This marks a significant step in the pursuit of international justice since it would be the first time an incumbent political leader would be indicted by this court.

It also reflects a remarkable turnaround in terms of accountability. Between 1945 and 1990, about 180million people were killed in conflict, often as a result of acts of genocide and crimes against humanity. However, with very few exceptions, there was no accountability for such atrocities. The position has changed. Whereas heads of state would have once regarded themselves as above the law, this is no longer the case. During the past few years former leaders such as Serbia's Slobodan Milosevic, Chile's Augusto Pinochet, Rwanda's Jean Kambanda, Peru's Alberto Fujimori, Iraq's Saddam Hussein and Chad's Hissene Habre faced legal processes relating to their (alleged) crimes. While these processes have each had varying degrees of success - the Saddam trial, for example, was unfortunately highly flawed - the point is that it would have been unthinkable even 10 years ago that leaders or former leaders such as these would have faced trial in such a public forum.

The Economist magazine last year quoted Libya's Muammar Gaddafi lamenting: "This means that every head of state could meet a similar fate. It sets a serious precedent." This is a direct consequence of the evolution of international criminal justice. Criminologists now talk about a Pinochet syndrome, where the senior political and military leaders of today and tomorrow can no longer ignore the rule of law and the reach of the various systems of national and international criminal justice.

Yet, despite these positive developments, the inescapable spectre of realpolitik hinders the progress of justice. There are many examples of this. Just last week, the UN Security Council rejected a proposal to impose sanctions against the Mugabe regime in Zimbabwe. (Russia, China, South Africa, Vietnam and Libya voted against it.) Radovan Karadzic and Ratko Mladic are still at large from the ICTY 13 years after the genocide at Srebrenica and will remain so unless Serbia changes its attitude towards that tribunal, something that is even less likely now the international community has openly supported the independence of Kosovo.

Even the work of the ICC is hamstrung by politics. The first trial, that of Thomas Lubanga Dyilo, a founder and leader of the DRC rebel group Union des Patriotes Congolais, was scheduled to begin late last month. However, much of the evidence on which the prosecution in that case is relying was provided on a strictly confidential basis by various UN agencies, under an agreement that prohibits the accused (and even the trial judges) from seeing it. Under those circumstances, it is difficult to see how a fair trial can take place and the trial chamber has therefore ordered the unconditional release of Lubanga. (That order has been suspended pending an appeal to the appeals chamber of the ICC.) In another situation before the court, some countries are supporting a proposal that the ICC drop its indictments against Joseph Kony, leader of the Lord's Resistance Army in Uganda, as a condition of a peace agreement being negotiated in that country.

In each of these examples, if the politicians win the day the many thousands of victims and their families who had been affected by the brutality of these people would be deprived of a sense of real justice. We must not allow this to happen.

In the end, therefore, the effectiveness of international criminal justice will largely depend on the efforts of states to demonstrate the requisite political will - backed by tangible resources and action - necessary to allow for proper accountability for those who commit gross violations of human rights. It is in this regard also that states have and will continue to play a crucial role. The ICC and other international tribunals have no police force and are, to a large degree, entirely reliant on states to effect the arrest of indicted individuals so they can be brought before an appropriate court to face trial.

States have another, even more important, role. Prosecuting the perpetrators of these crimes represents only half of the picture. Courts such as the ICC are significant in this process of justice and reconciliation, but their creation is not the panacea that will stop these atrocities from taking place. To prevent acts of genocide and other atrocities requires more than the establishment of a legal regime that can deal with the crimes once the killing has stopped. That is an important element in the matrix of international criminal justice but is based on an assumption that such acts will take place. What is needed is the sincere and determined political will on the part of all states to respect international law, to listen to the calls of those under threat and to ensure that crimes such as these do not occur.

Steven Freeland is associate professor of international law at the University of Western Sydney and a visiting professional at the ICC in The Hague. These are his personal views.