One measure may be the cadence of terrorist attacks. So far this year, more than 7500 people have been killed in more than 5000 incidents across four continents. That is a significant improvement on last year, when more than 15,000 people were killed in more than 11,000 terrorist attacks. Despite a clear desire to do so, Osama bin Laden and his central al-Qa'ida leadership have been unable to replicate the mass-casualty atrocities of the 2001 airlines plot against the US, nor can they get their hands on a nuclear weapon. Can we therefore say that terrorism is a declining security threat and the situation is better than when hostilities began?

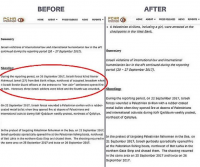

Public opinion in Australia supports this view. An Australian Strategic Policy Institute survey on national security and defence last year found terrorism had dropped to 13th out of 14 touchstone issues at the 2007 election. Two-thirds of Australians think terrorism is now a part of everyday life. Climate change is the new terrorism. But when we asked if the government was doing all it could to prevent a terrorist attack, the public's response was more equivocal. Only half thought the government was on the ball. Despite the investment of nearly $10 billion since 2001 in national security measures, 41 per cent of respondents said governments should be doing more. That there has not been a serious terrorist attack on Australian soil since the Sydney Hilton bombing in 1978 leads some to argue that the threat is so low, national security funding should be channelled elsewhere.

And in a crowded agenda where a growing number of issues including cyber security, energy security and organised crime compete for limited resources, the idea that we should be shifting the emphasis away from terrorism is gaining ground. This is not a view I share. The real danger is a growing sense of complacency over the nature and extent of the long-term threat from religiously motivated terrorism.

As Peter Clark of the British police said recently, "The current terrorist threat is of such a scale and intractability that we must not only defeat the men who plot and carry out appalling acts of violence. We must find a way of defeating the ideas that drive them."

The number of terrorist attacks across the world may have decreased, but the corrosive ideologies that drive international terrorism continue to gain traction from Somalia to the southern Philippines. And the focus of this ideological brainwashing is increasingly directed towards children. In Indonesia, the radical Islamist Hizb ut-Tahrir is focusing its attention on schools, providing reading materials and instruction to teenagers advocating the overthrow of secular democracy and the introduction of Islamic law and a caliphate.

Although such organisations stop short of promoting violence, the radicalising link between propaganda and terrorism has been well-established.

As internet coverage expands, so too does the extremist message. Hizb ut-Tahrir Indonesia runs a sophisticated website that rivals global news organisations. Teenagers are the greatest users of the internet, and interactive social networking websites provide terrorist groups with new opportunities to recruit and radicalise.

It is no surprise the terrorist organisation in Somalia is called al-Shabaab (the youth).

For the ideology to succeed it must constantly seek new recruits. As a new generation of terrorists is formed, the international community appears incapable of responding in a comprehensive, strategic way.

To date, the global war on terror has been split between 95 per cent military operations and 5 per cent ideological operations. That must be reversed, because it is winning the ideological war that will ultimately determine whether we succeed or fail against the present wave of religious terrorism.

Carl Ungerer is director of national security at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute.