Links

Sheba Medical Centre

Melanie Phillips

Shariah Finance Watch

Australian Islamist Monitor - MultiFaith

West Australian Friends of Israel

Why Israel is at war

Lozowick Blog

NeoZionoid The NeoZionoiZeoN blog

Blank pages of the age

Silent Runnings

Jewish Issues watchdog

Discover more about Israel advocacy

Zionists the creation of Israel

Dissecting the Left

Paula says

Perspectives on Israel - Zionists

Zionism & Israel Information Center

Zionism educational seminars

Christian dhimmitude

Forum on Mideast

Israel Blog - documents terror war against Israelis

Zionism on the web

RECOMMENDED: newsback News discussion community

RSS Feed software from CarP

International law, Arab-Israeli conflict

Think-Israel

The Big Lies

Shmloozing with terrorists

IDF ON YOUTUBE

Israel's contributions to the world

MEMRI

Mark Durie Blog

The latest good news from Israel...new inventions, cures, advances.

support defenders of Israel

The Gaza War 2014

The 2014 Gaza Conflict Factual and Legal Aspects

To get maximum benefit from the ICJS website Register now. Select the topics which interest you.

The B'Tselem Witch Trials

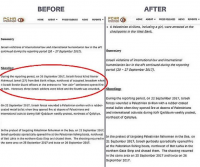

When the United Nations released the so-called Goldstone Report in September 2009, Israelis and their supporters around the world were astonished by the blunt words near its conclusion: “There is evidence indicating serious violations of international human rights and humanitarian law were committed by Israel during the Gaza conflict, and that Israel committed actions amounting to war crimes, and possibly crimes against humanity.” The report declared that virtually everything Israel had done during Operation Cast Lead—Israel’s attempt in late 2008 and early 2009 to stop Hamas’s rocket war on Israeli civilians—had been a crime. No single written attack on the Jewish state has been as damning, as prominent, or as influential. And yet the South African jurist Richard Goldstone and his team had only a few months to compile a report that runs to nearly 600 pages and makes hundreds of detailed accusations about the Israel Defense Force’s conduct of the war, and Goldstone himself made only a single four-day visit to Gaza. Where did they secure the evidentiary rope with which to hang Israel?

The report was largely compiled from material provided by what is often referred to as Israel’s “human rights community.” This vague euphemism refers to a coterie of groups and individuals that has evolved over the past decade into a highly politicized movement of dozens of nongovernmental organizations that operate in Israel and subject its government, military, laws, and people to relentless scrutiny and accusation. And, as first pointed out by NGO Monitor, the Goldstone Report relied most heavily on the largest and most prominent among them: the group known as B’Tselem. More footnotes in the report, 56 in all, cite B’Tselem as a source than any other. Indeed, as Jessica Montell, B’Tselem’s executive director, has said, B’Tselem “provided extensive assistance to the UN fact-finding mission headed by Justice Goldstone—escorting them to meet victims in Gaza, providing all of our documentation and correspondence, and meeting the mission in Jordan.”

In making such a profound contribution to the Goldstone Report, B’Tselem was performing the task to which it has truly dedicated itself: not the defense of human rights in the West Bank and Gaza, but the delegitimization of Israel and its existence as a Jewish state.

_____________

B’Tselem—“The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories”—was founded in 1989 by what the organization refers to as “a group of prominent academics, attorneys, journalists, and Knesset members” whose politics were overwhelmingly on the far left of the political spectrum. Its purpose was to “document and educate the Israeli public and policymakers about human-rights violations in the Occupied Territories,” and during the 1990s it largely focused on that internal mission. Yet with the onset of the Palestinian terror war in 2000 and Israel’s increasingly tough responses to it over the succeeding four years, B’Tselem’s mission shifted from trying to inform and influence the Israeli debate to becoming the primary resource for those journalists, officials, and activists who saw in Israel’s self-defense the full flowering of a new age of Israeli oppression and criminality.

B’Tselem employs Israelis, and there is no doubt that the major reason for its appeal—especially internationally—is due to the perception that it is an Israeli group exposing Israeli crimes in order to achieve a more just Israeli society. Yet almost its entire annual budget is provided by European governments and American foundations, such as the New Israel Fund and the Ford Foundation.

That money pays for 41 staffers who work primarily in two divisions, data and communications. Most of the 19 members of the data division are Palestinians who live in the West Bank and Gaza and supply a constant stream of anecdotes and testimony to the group’s Jerusalem headquarters, where a few researchers compile the information and the 10-person communications department packages and disseminates it to journalists, other NGOs, policymakers, and activists. B’Tselem mounts campaigns on certain issues, such as the supposed illegality of Israeli communities over the armistice lines of 1949 and the supposed illegality of West Bank checkpoints erected to interdict suicide bombers. “B’Tselem,” according to its own materials, “ensures the reliability of information it publishes by conducting its own fieldwork and research, the results of which are thoroughly cross-checked with relevant documents, official government sources, and information from other sources.” These reports have made B’Tselem the most famous and successful Israeli NGO. It is also one of the most ambitious. A list of “advocacy efforts” from its 2009 year-end report, for example, includes

a month-long, high-profile campaign using B’Tselem’s 20-year anniversary to draw attention to the urgency of the human-rights situation in the Occupied Territories; four Internet campaigns on Operation Cast Lead, security force violence, the siege on Gaza, and Road 443, which is barred to Palestinian use; four full-length publications, including Guidelines for Israel’s Investigation of Operation Cast Lead and Without Trial: Administrative Detention of Palestinians by Israel; 22 visual articles and films made available online; and 80 study tours and 176 briefings for policymakers, journalists, diplomats, and international organizations.

Today, B’Tselem conducts itself as though its true purpose is not trying to convince Israelis to change their policies from within, but rather aiding international efforts to pressure Israel to adopt the kind of policies Israelis themselves have repeatedly rejected in elections. To that end, in 2008 B’Tselem opened an office in Washington, which, according to a press release, it “expects to become the central clearinghouse for information about human-rights conditions in the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip for Member [sic] of Congress, the State Department, and other policymakers.” Or, as Anat Biletzky told a small campus audience in 2007 just after she stepped down as the group’s chairman of the board, “B’Tselem is now opening an office in D.C. because we think that there are two main targets here. One is American policymakers. The other is the Jewish community. And the two are not unrelated, as we have seen in Walt and Mearsheimer’s book.”

All of this work has certainly paid off. In 2004, as Biletzky told an interviewer, “B’Tselem is trusted by all sides. The Europeans of course. If the American Embassy wants information, they come to us. If Tom Friedman wants information, he comes to us.” The U.S. State Department can be added to the list of those who not only trust B’Tselem, but rely on the group uncritically. State’s annual “human rights report” on Israel reproduces B’Tselem claims and statistics, quite obviously without external verification, to such an extent that sections of the report simply read like a year-end summary of B’Tselem reports. The just-released report on 2010, for example, contains 26 references to B’Tselem and endorses its misleading Gaza casualty figures. And the group’s reports are a regular feature of media coverage of Israel. For example, Lawrence Wright’s lengthy 2009 account in the New Yorker of life in the Gaza Strip cited, entirely without skepticism, B’Tselem’s erroneous casualty statistics from Operation Cast Lead: “B’tselem has documented seven hundred and seventy-three cases in which Israeli forces killed civilians not involved in hostilities.”

What should have been obvious to an intelligent and worldly journalist such as Wright is the conspicuous tension in B’Tselem between the group’s wish to be perceived as an impartial guardian of human rights and its openly stated desire to build a case against virtually every security measure Israel takes, as well as against the Israeli presence, civilian and military, in the West Bank and in East Jerusalem. The irreconcilability of these two goals is evident on B’Tselem’s website, where it describes itself as a scrupulously apolitical organization that does “not weigh in on political matters, except to comment on their implications for human rights”—and at the same time also states that it “has worked successfully on both the political and public level to shape Israel’s national debate over policies regarding the Occupied Territories” and that it “acts primarily to change Israeli policy in the Occupied Territories.” Thus a basic question presents itself: Is B’Tselem a human-rights organization or a political group?

B’Tselem, in fact, is consciously trying to have it both ways, using human-rights rhetoric to conceal a radical and indeed anti-Zionist political agenda that would be met with far less sympathy were it honestly expressed. It is not an unintelligent strategy. Biletzky, for one, is proud of her organization’s innovative approach:

In April of 2003, we issued a report called “Landgrab,” which is the most comprehensive report ever on the settlements. It showed how the whole settlement project is a violation of human rights according to international law and the Geneva Convention. . . . It’s amazing because I think that conceptually it’s very creative to think of settlements as being a violation of human rights.

Creative it certainly is, especially because the claim is also based on a false premise, namely that every dunam of the West Bank is sovereign Palestinian territory and therefore any Israeli presence there amounts to illegal occupation. This argument has become the standard claim of those who demand the expulsion of Jews from the West Bank and East Jerusalem. Yet these have never been “Palestinian territory” according to the understanding of sovereignty under international law. For 500 years, the West Bank was ruled by the Ottoman Empire, then by the British Mandate, and then for 18 years by the kingdom of Transjordan. In 1988 Jordan formally renounced any claim to the territory. The West Bank is disputed territory, as both Jews and Arabs have lodged claims to it, and the peace process is supposed to be the forum through which those claims are negotiated and resolved.1 Yet “Landgrab” avoids all of this difficulty through a tautology: because Jewish communities in the West Bank are ipso facto a human-rights crime, “B’Tselem demands that the Israeli government act to vacate all the settlements.”

The fact that Israelis are living anywhere on the West Bank or in Gaza is the original sin for B’Tselem, the wellspring from which all other crimes emerge. Yet B’Tselem goes beyond even that point to argue that efforts made by Israel to defend its citizens against attacks by Palestinians operating in the West Bank and Gaza are in fact criminal acts under international law.

In a 2007 report on Gaza, for example, B’Tselem declared that, due to the restrictions on border crossings to prevent terrorist attacks, “Israel has turned the Gaza Strip into the largest prison on earth.” (Egypt, which also restricted its border to Gaza, was entirely absolved: “Israel controls all routes into and out of the Gaza strip,” B’Tselem improbably claimed. “No one can enter or leave without the army’s permission.”) The Gaza report was plastered with sensational photographs and pullquotes attesting to the horrors of life there, all of which, the group insisted, were Israel’s fault. This, despite the fact that Israel had pulled out of Gaza in 2005, did not interfere when Palestinian elections there gave the terrorist group Hamas the upper hand in 2006, and stayed out of it when Hamas staged a coup in Gaza against the Palestinian Authority and took charge of the strip in 2007. B’Tselem acted as though all that was meaningless. “Whether you call it an occupation or not,” the report says, Israel still “must safeguard the rights and needs of the people there.” Elementary logic would seem to dictate that Hamas, not Israel, was responsible for safeguarding the rights and needs of the people there, and that Hamas, by attacking Israel on a daily basis, bore responsibility for the problems created in Gaza by the state of war it insisted on maintaining.

Not according to B’Tselem. The group absolved Hamas of any responsibility for conditions in Gaza, never mentioned its goal of destroying Israel, blamed Israel entirely for the border restrictions that only followed Hamas’s attacks (many of which targeted the border crossings themselves), and even provided the terrorist group with an important incentive to continue its rocket war. In this war, which Hamas wages intentionally from civilian areas of Gaza, Palestinian civilians are occasionally killed by Israeli return fire. Yet instead of condemning Hamas for employing civilians as cannon fodder, B’Tselem suggested that their deaths were the result of an intentional Israeli strategy: “Targeting civilians is absolutely prohibited, even if the purpose is to protect other civilians.” It is not an exaggeration to say that B’Tselem’s report on Gaza, despite its perfunctory call for Hamas to stop firing rockets, is in substance a long apologetic for both Hamas’s abuse of Gazans and its war on Israel.

Even when Israel acts in ways that seem to accord with B’Tselem’s wishes, the organization declares the state in the wrong. In 2004, as Israel debated whether to carry out a full withdrawal of its civilians and military from Gaza, Montell wrote that “we must applaud any level of disengagement.” The report her organization issued three years later, after disengagement, was stamped on every page with the slogan: “Israel cannot disengage from its responsibility.”

Also in 2007, the group released a 118-page report titled “Ground to a Halt.” It declared every single Israeli checkpoint and road restriction in the West Bank a multifaceted violation of international law. It may be difficult to understand how a checkpoint erected to protect the human rights of Israelis can itself be a human-rights violation, but that is precisely what B’Tselem discovered. The group offered two main arguments. The first had to do with the balance between Israeli security and Palestinian inconvenience:

The state must prove that there is a rational connection between the infringement of freedom of movement and achieving the security objective sought to be achieved, that it is not possible to achieve the security objective by a less harmful means, and that there is a proper relationship between the harm caused to those whose freedom of movement is restricted and the security purpose achieved as a result of the infringement.

Israel failed every aspect of this test, according to B’Tselem. But the test was, in any case, mere window-dressing for the group’s real argument, which is the same one offered in “Landgrab”: Israelis have no right to live anywhere in the West Bank. And not only that, Israel therefore has no right to protect them. Or as B’Tselem stated more artfully:

This consideration [of protecting Israeli civilians from attack] does not exist in a vacuum. It is derived from broad, improper political considerations without which the need to impose the restrictions on Palestinian movement would never have arisen. The main improper political considerations relate to Israel’s desire to perpetuate the settlements. . . . The establishment of the settlements in the West Bank, a long-established policy of the Israeli government, flagrantly contravenes international humanitarian law.

B’Tselem ended with these words: “The conclusion is, therefore, that those restrictions on movement, whose primary justification is ostensibly ‘protection of the lives’ of Israelis in the West Bank, are illegal.”

But surely an organization concerned with the rights of civilians would acknowledge that Israel has a duty to protect its citizens, say, in Tel Aviv, from Palestinian suicide bombers who start their journey in the West Bank? No. When considering these matters, B’Tselem conveniently applied the international-law principle of proportionality, which was originally devised to determine the acceptable level of firepower used in military attacks during war, to West Bank restrictions. Here, too, B’Tselem ruled that Israel was guilty:

Even if the group restrictions have a certain measure of effectiveness in achieving their security objective, it is hard to find a reasonable relationship between the added benefit that the army contends they provide and the unreasonable harm that they cause to the local population.

And so, even if the security measures worked, they were still “unreasonable” and therefore a violation of international law. What would be a “reasonable” security measure, according to B’Tselem? Armored transportation for Jews: “Over the years, the authorities preferred to ignore alternatives that would provide proper protection for the settlers, such as protected, bulletproof vehicles used by settlers or by having them use protected, bulletproof public transportation.”

B’Tselem also claimed that checkpoints and road closures constitute “collective punishment.” That was a startling charge, because the term was devised by the authors of the Geneva Conventions in response to the Nazis’ practice of slaughtering entire villages as punishment for the offenses of individuals. B’Tselem has led the way in transforming that prohibition into one that precludes any Israeli security measure that affects any Palestinian not personally involved in attacking Israelis. Montell, for example, has gone so far as to declare even Israeli air-force flights over Gaza a war crime, writing in 2006

that the clear intention of the practice is to pressure the Palestinian Authority and the armed Palestinian organizations by harming the entire civilian population. It is a form of collective punishment, which is blatantly illegal.

All in all, B’Tselem has been an innovator in manipulating traditional definitions of international law, no matter how concocted and implausible, to suit an assault on whatever Israeli practice B’Tselem wishes to condemn. The group does admit in its reports that Israel has a right to protect its citizens. But it is a right that B’Tselem affirms only in theory, never in practice.

_____________

Another of B’Tselem’s major activities is compiling statistical reports that it hopes will demonstrate, with empirical credibility, Israel’s abuses. After Operation Cast Lead, for example, B’Tselem made headlines with a report claiming that a majority of Palestinians killed during the war were civilians, attacking the accuracy of the IDF’s numbers and undermining the perception that the IDF had fought carefully in Gaza.

During the war, B’Tselem reported, 1,387 Palestinians were killed, 773 of whom “did not take part in the hostilities” and only 330 of whom were combatants. This curious phrasing, which was shortened in media coverage simply to “civilians,” was in fact a bit of sophistry employed to conceal B’Tselem’s results-oriented approach to statistics. The IDF’s own investigation, by contrast, counted 1,166 Palestinians deaths, of whom 709 were terrorists and 295 were civilians—a commendable ratio given that much of the war was fought, by Hamas’s design, in civilian areas.

B’Tselem arrived at such a high number of “civilian” deaths by adopting a definition of “combatant” that transformed terrorists into civilians. The group only counted those “who fulfill a continuous combat function” as legitimate targets. Such people include full-time members of the Hamas “armed wing,” and virtually nobody else—not Hamas policemen and not Hamas political and spiritual leaders, financiers, propagandists, recruiters, weapons smugglers, or support personnel. By adhering to this definition, the United States would be barred from killing many members of al-Qaeda.

B’Tselem also claimed that 320 civilian minors were killed. Yet the group’s own statistics on the male–female ratio of those minors strongly suggests that many of the older minors were in fact combatants. As documented by two Israeli researchers who examined B’Tselem’s data, the male–female ratio of those in the 11-and-younger group was nearly 1:1. Yet as the age rose, so did the gender disparity, to the point where the male-female ratio for 17- and 18-year-olds was more than 6:1. If Israel had been indiscriminately attacking civilians, how would it have been possible for such an overwhelming number of them to have been males?

Recently, B’Tselem’s statistics were repudiated by an unlikely source, the “interior minister” of Hamas. In November 2010, he told the London-based Al-Hayat newspaper that between 600 and 700 Hamas militants had been killed during the war—double the number claimed by B’Tselem, and almost exactly the number reported a year earlier by the IDF.

_____________

In its 2009 year-end report, B’Tselem proclaimed that “in the past two decades, B’Tselem emerged as the gold standard of human-rights research, serving as an extremely reliable source of information in a contentious and polarized climate.” Yet some of the most polarizing figures in Israel are members of B’Tselem. To understand why B’Tselem acts the way it does, one must understand its members. An organization, after all, is little more than a collection of the people who lead and staff it.

Shortly following its self-proclamation regarding accuracy and moderation, an Israeli columnist discovered that the group’s data-coordination director—one of the most important positions in the organization—had posted a number of curious entries on her personal blog. “Israel is committing Humanity’s worst atrocities,” Lizi Sagie wrote. “Israel is proving its devotion to Nazi values. . . . Israel exploits the Holocaust to reap international benefits.” Israelis, she noted, “don’t erect gas chambers and extermination camps, but if there were any, how many people would actually resist it, and not only in their hearts?” And she admonishes, “In the name of the State of Judaism we have stolen lands, murdered, starved others . . . have created ghettos [for] all kinds of ‘others’ [and] allowed fascists to raise their heads.”

Sagie resigned from B’Tselem following the exposure of these statements. But they are only the most extreme version of a point of view held by B’Tselem’s own leaders. Consider the cases of Jessica Montell, the current executive director; Anat Biletsky, who served on B’Tselem’s board starting in 1995 and was its chair from 2001 to 2006; and Oren Yiftachel, the current co-chair of the board.

Montell was born in Berkeley, California, received a degree in women’s studies at Oberlin, and then a master’s in international relations at Columbia. She immigrated to Israel in 1995 to work for B’Tselem and became its executive director in 2001. In a 2003 interview, Montell claimed that “in some cases, the situation in the West Bank is worse than apartheid in South Africa.”

That same year, Montell appeared at a roundtable discussion at the American Colony Hotel, the favored East Jerusalem hangout of international journalists, UN officials, and the NGO set. There she expressed the opinion that the murder of hundreds of Israeli civilians in suicide bombings was problematic largely because of Israel’s attempts to prevent more carnage. “This current intifada,” she argued, “has greatly exacerbated Israel’s human-rights violations. The current reality is affecting Palestinian human rights in every sphere, and virtually all Palestinians, certainly if we talk about restrictions on freedom of movement. It’s the most insidious form of human-rights violations.” Israel had succumbed, she continued, to a “security hysteria” that created a “lack of any sort of recognition of the humanity and rights of Palestinians.”

Expanding her attack to include almost the entirety of the Israeli population, she elaborated on what has become a standard talking point for those who share B’Tselem’s view of the conflict: Israelis are so consumed by racism and irrational fear that they are willing to engage in essentially limitless abuse of Palestinians in order to protect themselves.

Panelist: The general public is willing to sacrifice most or all of the human rights of Palestinians in exchange for some vain promises of security.

Montell: I agree. Our big challenge is to articulate a human-rights message in the face of this security hysteria, to come forward with the message that not everything is justified in the name of security, that the whole idea of security has to be examined—what we mean by it, what’s justified, what ultimately is going to achieve our security—all those questions that are swept under the carpet in Israeli society.

Montell concluded with a thought that, when stated by non-Jews, is generally viewed as anti-Semitic: “It’s the legacy of Jewish history that our own security concerns are manipulated to act as some sort of blank check for all Israeli government policies.”

The most fascinating part of the discussion, however, unfolded when Montell was encouraged by the moderator to consider “abuses of human rights inside Palestinian society.” Given an opportunity to balance her accusations against Israel, Montell answered instead:

In general, there has been a collapse of rule of law inside Palestinian society. The police stations and jails basically no longer exist and the police force no longer has freedom of movement within the territories. During parts of this intifada, the Palestinian police, or anyone wearing a uniform, were automatically targeted by Israel. Obviously, that is going to have very dramatic repercussions on the society as a whole.

For Montell, then, even Palestinian abuse of other Palestinians is Israel’s fault.

In 2008 Montell wrote a piece for Tikkun in which she explored her discomfort with Israeli Independence Day. “I prefer to think of myself as a citizen of the world,” she wrote, “and, having been born and raised in the United States before moving to Israel fifteen years ago, I ‘know’ and am full of criticism for both. Patriotism doesn’t come so easy to skeptics like me.” Indeed.

Then there is the case of Anat Biletzsky, a philosophy professor at Tel Aviv University. As she told a Brooklyn newspaper in 2004 about the history of her involvement in anti-Zionist activism, which long pre-dates B’Tselem: “The Communist party was not Zionist; it was Jewish and Arab. That was its main plank, which was very important to me. I worked for those parties during elections.” Biletzky—who was chair of the board of B’Tselem and its most prominent public face during a period that included the Palestinian suicide-bombing war, the Gaza disengagement, the Lebanon War, and the beginning of the Hamas rocket war—shaped B’Tselem into the aggressive, activist force that it is today. Her record of activism while serving as the chair of B’Tselem displays astonishing, serial antagonism to the Jewish state.

In 2002, after two years of Palestinian suicide bombings had left hundreds of Israelis dead, the IDF entered the West Bank in order to, among other things, protect the human rights of Israeli civilians to not be maimed and murdered. Biletzky responded by organizing a petition of academics “to express our appreciation and support for those of our students and lecturers who refuse to serve as soldiers in the occupied territories” and to “help students who encounter academic, administrative, or economic difficulties as a result of their refusal to serve.”

Later in 2002, as the United States contemplated invading Iraq, Biletzky signed a bizarre petition that read, “We are deeply worried by indications that the ‘fog of war’ [in Iraq] could be exploited by the Israeli government to commit further crimes against the Palestinian people, up to full-fledged ethnic cleansing.” It concluded by calling on the “International Community” to take “concrete measures” to prevent Israeli “crimes against humanity.”

Biletzky’s activism reached its apogee in 2004, when she helped write what is known as the “Olga Document,” a rambling tract named for the location in Israel where it was written. Israel, the letter says, is a “death trap” and “the biggest ghetto in the entire history of the Jews”; “military operations and wars has [sic] become the life-support drug of Israel’s Jews.” It goes on to state that “we are living in a benighted colonial reality—in the heart of darkness”; and that Israel seems “determined to pulverize the Palestinian people to dust” by subjecting them to “the nightmare of apartheid, the burden of humiliation and the demons of destruction employed by Israel unremittingly, day and night, for 37 years.” Out of “racist arrogance,” the document claims, Israelis across the political spectrum “depict the Palestinians as subhuman.”

The Olga Document continues: “We are united in a critique of Zionism, based as it is on refusal to acknowledge the indigenous people of this country and on denial of their rights, on dispossession of their lands, and on adoption of separation as a fundamental principle and way of life.” Besides adopting the self-evidently racist claim that only Arabs are “indigenous” to the land of Israel, Biletzky also called for the repeal of all laws and the end of all practices that make Israel a Jewish state. This, she said, along with creating an Arab majority in Israel through the Palestinian “right of return,” would finally absolve Jews of the moral stain that is Israel.

Biletzky has also acknowledged that she has been working to end Israel as a Jewish state since the late 1960s. She stated that “Israel [today] is like the Nazis or like Germany in ’34” and that life for Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza “is something that I do not hesitate to call a concentration camp.”

Biletzky is not merely an apologist for terrorism. At times, she has given terrorists moral support, as she did in the case of Azmi Bishara. He was a member of the Knesset from the Balad Party, an anti-Zionist Arab faction. In 2006, Bishara fled Israel after coming under investigation for espionage and high treason. When the gag order on the case was lifted in May 2007, it was revealed that Bishara had acted as a paid informant for Hezbollah during the Second Lebanon War, apparently helping the group select targets in Israel for missile attacks. It was also discovered that he had stolen millions of shekels from Arab charities. Biletzky responded to these devastating revelations by publishing a statement of solidarity in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz that read, in its entirety, “Azmi Bishara—we are brethren.”

Throughout her history of apologetics for violence and terrorism against Israel’s Jews, as well as her advocacy for the dismantling of the Jewish state, Biletzky has always been called a human-rights activist. For reasons that may be disturbing to contemplate, the journalists who eagerly report her organization’s accusations against Israel have never taken her biases into consideration when assessing the veracity of B’Tselem’s accusations. Most telling of all, perhaps, at no point did members of B’Tselem itself—its board, its employees, or its army of supporters—protest the extremism in its own ranks.

The situation is no better today. In 2006, Biletzsky stepped down as chair and has been replaced by two people: Gilad Barnea, an attorney who avoids political statements, and Oren Yiftachel, a professor of “political geography” at Ben-Gurion University. Yiftachel is one of Israel’s most outspoken anti-Zionists and calls his country “an ethnocratic regime” and a “Judaization project [that] has caused the pervasive dispossession of Palestinian-Arabs.”

His signature has appeared with Biletzky’s on many of the most extreme anti-Israel petitions of the past decade, such as a 2001 letter they signed endorsing Palestinian terrorism and calling for a “peace force” to stop Israel from defending itself: “We regard Palestinian violence as being, on the whole, a legitimate revolt against colonial occupation,” the statement read. “We call for an immediate international intervention to stop the killing and wounding of human beings who are exercising their elementary right to claim political freedom.”

Yiftachel also signed the 2004 Olga Document and a petition dated January 5, 2009, in the midst of Operation Cast Lead, that called on the UN Security Council and the EU to undertake a “massive intervention” to stop “Israel’s atrocities.” After the war, he published an article titled “The Jailer State” in which he argued that Hamas’s rocket war on Israeli civilians should “be perceived as a prison uprising, currently suppressed with terror by the Israeli state.”

Such expressions of furious contempt for Israel contrast sharply with B’Tselem’s rather successful attempt to identify itself as a source of Israel’s democratic strength. As Jessica Montell once told an American audience, her group is “the best evidence [for] the vibrancy of Israeli democracy”; or as B’Tselem’s spokeswoman wrote in the Jerusalem Post, “Israel must remain a strong, vibrant democracy.” That many in B’Tselem view this democracy as racist, belligerent, and illegitimate is an irony apparently lost on its defenders. Indeed, Israel is so open a society that its leading “human-rights” organization has been led for the past decade by two people who are open supporters of terrorism against it.

_____________

B’Tselem is merely one player, albeit a leading one, in a political movement that has developed over the past decade that seeks to place the very legitimacy of the Jewish state in question. It is joined by dozens of other groups in Israel and abroad that operate under the pretense of promoting human rights and civil society. The proliferation of these NGOs appears from the outside to be an independent and organic response to the worsening of real problems in Israel, but in fact the groups are closely allied. They have shared goals, shared funders (primarily European governments and the New Israel Fund in the United States), coordinate their work closely, defend each other from criticism, and collaborate on campaigns to promote specific accusations.

The tactics of the ideological war they are waging are unmistakable. The groups relentlessly accuse Israel of committing war crimes, human-rights offenses, and violations of international law. They champion the Palestinian cause and the Palestinian narrative of victimhood and Israeli oppression. They supply the highly massaged “facts” and claims that animate journalistic, diplomatic, and political activism against Israel, such as the Goldstone Report. They advocate for “lawfare” against Israeli officials—that is, prosecuting them for war crimes in European courts. And they argue either openly or by implication that Zionism itself—the existence of a Jewish state—is undemocratic, oppressive, and racist.

This war of delegitimization is so dangerous because it is targeted precisely at the heart of Western support for Israel—the belief in Europe and especially in America that Israel is not only a legitimate nation-state but also an exemplar of Western liberal values, deserving of the free world’s support and its protection in the face of constant attacks. The genius of the NGO movement is its promotion of Israelis themselves to make the case against Israel. Who better to convince Westerners that they are wrong to admire Israel than Jews feigning concern over Israel’s moral standing?

The story of those Israeli Jews who have made careers out of attacking Israel’s right to exist, such as Biletzky and Yiftachel, illustrates the degradation of the once mighty Israeli peace movement. Originally, the movement sought legitimacy and prominence in Israeli politics, and received it for a time—and because it was part of the political process, it was constrained by the need for electoral support and popular legitimacy. Yet the collapse of the Oslo Accords in 2000 and the Palestinian terror war that followed presented the peace movement with an existential crisis: With whom, exactly, were Israelis supposed to make peace? The withdrawals from Lebanon in 2000 and Gaza five years later, and the entrenchment in the vacated territory of Iranian-backed terrorist groups, further disillusioned Israelis and called into question the central proposition of the peace movement: if Israel makes the right concessions, peace will follow. And so, over the past 15 years, the peace movement has fallen from a position of influence in Israeli politics to one, today, of irrelevance, an anachronism that no longer has realistic answers to Israel’s problems.

What remains of the peace movement is a white-hot core of activists who refuse to acknowledge their failure and yet cannot gracefully recede from the political stage. They have discovered an innovative formula for rebuilding their political relevance completely outside the democratic political arena: reconstitute themselves as NGOs and conceal their political agenda in the apolitical rhetoric of human rights and international law. In this guise, the peace movement no longer has any need to win elections or offer a serious platform for governance. The NGOs instead position themselves as a blunt opposition force working against mainstream Israeli society, which is viewed as unsophisticated, provincial, racist, and stricken with “security hysteria.” This “human-rights community” has thus not only opposed every consensus Israeli security measure—Operation Defensive Shield during the

intifada, the security fence to stop suicide bombers, the targeted killings of terror-group leaders, the Lebanon War, and the Gaza War—but has branded them war crimes and human-rights violations for which Israel should be punished.

In these circumstances, where there is no point in trying to succeed at the ballot box, leftist Israeli activism now directs itself internationally in the hopes that fomenting a narrative of Israeli criminality will invite enough sanction and condemnation from Europe, the United Nations, and America to force Israel to accede to the demands of these otherwise powerless radicals.

The policies they support would constitute nothing less than Zionism’s destruction. And they apparently have no compunction about seeking its destruction from without, since they have learned to their disappointment and rage that Israel is too strong a nation to allow itself to be destroyed from within.

# reads: 159

Original piece is http://www.commentarymagazine.com/article/the-btselem-witch-trials/