Rabbi Dr Jonathan Romain wrote to 823 families in his shul (Photo: Getty Images)

Rabbi Dr Jonathan Romain wrote to 823 families in his shul (Photo: Getty Images)

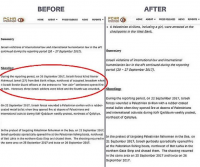

On October 30, just after the election was announced, I broke ranks with the longstanding, unwritten rule that clergy in Britain do not intervene in party politics.

It is common for bishops, rabbis and imams to speak out on specific issues about which they feel strongly — from homelessness to climate change — but never to back or berate one particular party.

It would compromise their status as neutrals able to minister to the entirety of their flock, and was not considered the British way of doing things — unlike in Israel or America, where politics and religion often form an unholy mix and are not admired over here.

However, I felt that the situation Britain now faced was so dire with Jeremy Corbyn as a possible Prime Minister that it was no time for political correctness.

Until Mr Corbyn, antisemitism had been largely limited to the extreme right and street graffiti. It was astonishing, therefore, to see a mainstream political party being tainted with the same brush.

It was not just the threat to Jewish life, but a negation of British values. I could see concepts such as tolerance, communal harmony and mutual respect beginning to be an endangered species. Other parties were also at fault, but none so wilfully as Corbyn-led Labour.

So I wrote an email to all members of Maidenhead Synagogue — which covers several different constituencies throughout Berkshire and Buckinghamshire, including Labour ones — suggesting they vote for whichever party was most likely to defeat Labour in their particular area.

There was an enormous response, far beyond anything that I have ever experienced when dealing with other controversial issues, from mixed-faith marriages to faith schools to assisted dying.

What was even more astonishing was the total disconnect between reactions by my community and those of fellow rabbis.

For the former, and Jews throughout the UK who got in touch after reading about the email in the JC, there was almost overwhelming support.

No one was suggesting that Mr Corbyn was a Nazi or was about to introduce anti-Jewish legislation, but when you have lost one in three of your family in living memory, you get nervous at the slightest whiff of antisemitism.

It was no wonder that some Jews had thought of packing their bags and leaving England if Mr Corbyn had come to power. If you have been nearly annihilated, you do not hang around for more.

I articulated the deep sense of unease they felt. Whatever their political views (and many were long-standing Labour supporters), never before had antisemitism been on the agenda as a political issue, and they felt it needed calling out.

By contrast, virtually all rabbis (the one public exception being Yuval Keren), reckoned I had made a major error: either because they did not think Corbyn was a danger, or because they agreed with my analysis, but thought I had crossed a red line in criticising him.

I was also accused of stoking fears in the community instead of trying to calm them down. It begged the question of whether rabbis should always seek a middle path or sometimes take the high road?

In addition, it meant that rabbis of all denominations now felt pressurised by my action to take a stand themselves. Their own congregants began asking “What do you advise?”

I do not know if that applied to the Chief Rabbi, but I am sure it made his subsequent intervention easier to contemplate.

Did “coming out” make a difference to the national vote? Yes it did. Mr Corbyn’s failure to tackle antisemitism did not just worry Jewish voters, but alerted many others to the fact that something was wrong within Labour.

Much had been made of him being a man of integrity — a person in the political wilderness who had stuck to his principles throughout his time on the backbenches. Now people began to realise why he had been in the wilderness for so long.

The carefully constructed halo around him began to be dented and rot away. As one person told me: “If he can have a blind spot about antisemitism, what other blind spots does he have?”

Among the many messages of the election is that antisemitism — or any other prejudice — has no place in this green and pleasant land.

On a personal note, I have no regrets at going public but, respecting the traditional position, I shall now return to observing non-partisan politics. I hope that no rabbi will have to cross that red line again.