Ever since the establishment of the Anti-Defamation League in 1913, institutions of American Jewry have been actively fighting antisemitism. But, like those irritating children’s toys, as soon as it’s knocked down in one place, it seems to pop up in another.

Have the efforts to fight antisemitism in modern society been effective? Is there a better strategy?

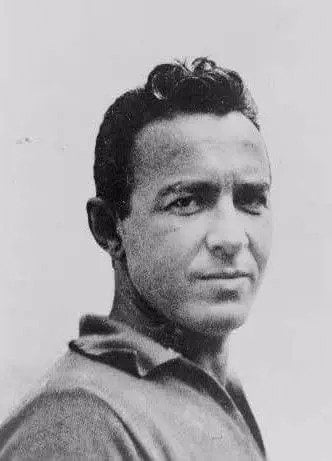

The Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory, experienced antisemitism throughout most of his life. In his childhood in Ukraine, under Czarist rule, he hid from the terror of pogroms, only to be confronted with an even more virulent form of persecution as a teenager, under Soviet rule. He watched the rise of the Nazis from a front-row seat, while studying at the University of Berlin between 1928-1932. One of his two brothers was murdered by the Nazis, as well as his wife’s sister and brother-in-law. His credentials as a victim of antisemitism could fill a short book.

The Rebbe’s leadership as a whole, which began in 1950, was framed by the Holocaust, and thousands of high and low-profile incidents of antisemitism—in untold forms, at hundreds of locations across the world—accrued during the four-and-a-half decades that followed.

In 1964, the novelist and social critic Harvey Swados asked the Rebbe if the Holocaust could happen again.

“Tomorrow morning,” the Rebbe replied.1

In fact, on several other occasions, the Rebbe cited the declaration of our sages, “It is a rule that Esau hates Jacob,”2 meaning, antisemitism is basically a rule of physics; it’s hard-wired into the world.

But despite his personal experiences with antisemitism, despite that he was not naive about the fact that it exists even in America today, and despite the fact that it’s seen as an urgent issue—drawing considerable attention in Jewish communal life, and considerable resources from Jewish institutions—it’s clear that the Rebbe was not simply sidestepping the issue.

Rather, the “non-attention” is actually a key aspect of how the Rebbe believed antisemitism should be handled. He refused to allow it to occupy center stage, nor to become a focal point of any kind.

The “non-attention” is a key aspect of how the Rebbe believed antisemitism should be handled. He refused to allow it to occupy center stage.In this brief essay, we will look at several rare occasions when the Rebbe addressed matters of antisemitism, to see what practical guidance we can draw. We’ll explore the Rebbe’s view on the cause of antisemitism, and we’ll look at how he sought to avert it, along with some practical dos and don’ts in dealing with antisemites.

We won’t have a how-to guide for every situation, but at least we will be working from a position of knowledge. Which matches the Rebbe’s style perfectly—help us see the 50,000-foot view; hopefully, we can handle the specifics from there.

The Roots of Antisemitism

Purim of 1965 was a rare occasion when the Rebbe spoke about anti-semitism in-depth. He discussed why they hate us, and provided an overview of the Jewish approach to combating it throughout the generations.

Purim is, of course, the classic antisemitism story. Haman presented to Achashverosh an ambitious but very real plan to kill every Jew in the entire world in one day, offering ten-thousand silver pieces—today’s equivalent of several billion dollars—to pay for the expenses of getting the job done.

Achashverosh agreed to the plan, but told Haman to keep his silver.

The Talmud3 uses a parable to explain an exchange between Achashverosh and Haman:

There were once two men, who each owned a field. One had a mound in the middle of his field; the other, a ditch.

The owner of the ditch, noticing the other’s mound of dirt, said to himself, “How I wish I could use that dirt to fill my ditch; I would be willing to pay for it!”

Meanwhile, the owner of the mound thought to himself, “If only I could use that ditch as a destination for my troublesome pile of earth!”

One day, they met one another. The owner of the ditch laid out a proposition: “How about you sell me your mound, so I can fill in my ditch with its dirt?”

To which the latter replied, “Take it for free—if only you had done so sooner!”

The Rebbe asks: True, Achashverosh had a problem to deal with—an empire of 127 nations, with many Jews living amongst them. They were a nuisance, a “mound of dirt,” in his valuable field.

But what does Haman’s “ditch” represent? And in what sense does eliminating the Jews parallel the leveling of a field? You’d think that you fill a ditch by adding to the field, not by eliminating something?

The Rebbe explains that the underlying cause of the condition called antisemitism has two precursors:

One antisemite says to the Jew, “You don’t belong in my world. You people are a mound in my field. Get out!”

Achashverosh fits the description that the Midrash assigns to Esau, who said to Jacob, “Didn’t we agree that this world is mine, and the next world belongs to you? Why are you mixing into the affairs of this world? You belong in your synagogue dealing spirituality!”

For Haman, however, the problem runs deeper.

Why does the Jew irk him so much?

Because the Jew exposes a gaping void in this person’s life. G‑d gave the Torah to the Jews, and with it, a higher purpose. When he sees the Jew, he cannot escape the ditch in his own field. This latter problem is the void that constitutes this latter antisemite’s “Jewish problem.”

When the antisemite sees the Jew, he cannot escape the ditch in his own field. This is the void that constitutes this antisemite’s “Jewish problem.”If he really wanted, he could lift himself up, but he doesn’t want to do the work. So he chooses a far simpler solution: Get rid of the Jew entirely. The “ditch in his field,” his void, will be leveled when there’s no one to remind him of his own emptiness.

It doesn’t matter what the Jew does or doesn’t do. It won’t help to stop acting Jewish, to make Shabbat on Sunday, to eat, speak and dress the same as everyone else. These two causes of antisemitism have nothing to do with your actions. A Jew is a representation of Torah, and your very existence makes the antisemite feel inadequate.

So what can we do about it? Here are the Rebbe’s responses to several cases of antisemitism:

Pompidou and the Protestors

After the 1967 Six-Day War, the French president, Charles de Gaulle, decided to stop selling arms to the countries which had been involved in the conflict. In truth, De Gaulle—who had made statements to the press about how the Jewish people “through the ages” had “provoked” and “caused ill will” in certain countries—was moving against Israel alone; the Arab countries were being supplied by Russia. The Jews—“an elitist and dominating people”—were deeply offended by his words. Jewish and non-Jewish leaders sharply attacked his blatant antisemitism.

In 1970, France, now under de Gaulle’s successor, Georges Pompidou, suddenly announced the sale to Libya of 50 Mirage ground-attack aircraft, and later another 30 Mirage III‐E interceptors and 20 trainer reconnaissance planes. This constituted a major threat to Israel, as these could easily be resold to Egypt or Syria (and in fact, that, precisely, was the plan). When President Pompidou visited the United States, there were a series of strident demonstrations organized by Jews in Washington, DC, New York and Chicago.

As Pompidou stepped from his limousine onto the red carpet to wave and smile at the crowd, he was greeted with a chorus of boos, hecklers, and chants of, “Shame on you, Pompidou!”

The protests caused to a huge diplomatic ruckus and, if not for a hastily arranged trip to New York by Nixon himself, Pompidou’s visit would have been entirely derailed.

Several months later, in an address that can loosely be termed, “How to Handle Antisemites in Public Office,” the Rebbe addressed the fact that the president of France was confronted publicly by protesters who hoped that the French government would be intimidated into cancelling the ban on weapon sales to Israel.

Officially there was an "embargo," but France was, in fact, selling weapons to Israel. But only small arms, items that could be shipped without publicity. But after the protests, he canceled small arms sales, as well.

After some time, when the protests quieted down, Israel once again began dealing quietly with him, and Pompidou managed to extract three hundred Jews from Egypt! No protests, no publicity, no issues!

The Israeli government asked the newspapers not to write about it [in order to protect Pompidou from pressure by foreign governments and his French constituents]. We know about this only from non-Jewish newspapers.

This demonstrates clearly that the only way to deal with an antisemite is not by coming to him every day and shouting: Listen here, you are an antisemite! Listen here, you are a thief, a murderer, etc.! Rather, speak to him in a diplomatic way.

He knows well what they think of him, but he is a human being after all and behaves like a human being.

Once Pompidou was treated this way, 300 Jews were extracted from Egypt and Israel once again began receiving arms from France.4

In a different talk that same year, the Rebbe said that he had asked a leading activist, “Why are you running around and crying antisemitism, when you see it’s simply not effective in creating change?”

The fellow replied, “I figured out ten years ago that is a good modus operandi, and I don’t have time to rethink it. Stop telling me what to do.”

This demonstrates clearly that the only way to deal with an antisemite is not by coming to him every day and shouting: Listen here, you are an antisemite! Rather, speak to him in a diplomatic way.Efforts to shine a spotlight on antisemitism often succeed in achieving only one thing, the Rebbe stated, with a tinge of irony: attracting attention to the individuals or organizations leading those efforts.

(It’s important to note that certain situations clearly demand a different response. For example, the Rebbe established a very vocal and assertive approach to Israel and its relations with its antisemitic neighbors and other foreign nations; how it must defend itself by all means, without apology, and how Israel must be so strong militarily that her enemies are afraid to attack. These are subjects for a different essay.)

Jesse Helms and Friendship

For the duration of his first two terms in the Senate, 1972-1984, US Senator Jesse Helms (R-NC) was a staunch opponent of Israel’s cause. In 1973, he proposed a resolution demanding that Israel return the West Bank to Jordan. During Israel’s 1982 war with Palestinian terrorists in Lebanon, he demanded that the United States sever diplomatic relations with Israel.

A year or so later, circa 1983, Senator Helms took part in a Friends of Lubavitch event in Washington. In an interview with JEM’s My Encounter with the Rebbe project, Professor Alan Dershowitz described what he found unacceptable about Senator Helms’ participation:

When I was involved in politics, in civil rights and human rights, the enemy of civil rights and civil liberties was Jesse Helms, the United States Senator from North Carolina. He stood against everything that I stood for and many of my friends and colleagues stood for.

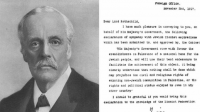

And so I was a little surprised, disappointed, when Jesse Helms was honored by the Rebbe and Chabad, and so I wrote a very polite letter to the Rebbe—who I had met previously a number of times—respectfully wondering why they chose to honor a man who was against integration, was against gay rights, women’s rights, equality for all.

The Rebbe wrote back a very poignant and very powerful letter saying we honor not only to recognize the past but to influence the future, and watch carefully to see whether or not we have had an influence on Jesse Helms.

In a three-and-a-half-page letter, the Rebbe explained to Professor Dershowitz that Senator Helms had attended an event at the Capitol, along with other senators and congressmen, in order “to pay tribute to a Jew and a Jewish movement.”

The Rebbe wrote that he’s “long been concerned about the state of our nation’s public schools, the American family and society,” and the event was geared to upgrading the ethical and moral foundations of education.

After a full two pages, the Rebbe signs off — and then there’s a one-and-a-half page postscript. (Note: Always watch out for the Rebbe’s PSs!) An excerpt:

I trust you will agree that in regard to persons of influence, whether in Washington or elsewhere, the first objective should be to persuade and encourage such a person to use his influence in a positive way in behalf of any and all good causes which are important to us. We should welcome every public appearance which lends public support to the cause, especially when there is a likelihood that it may be the forerunner of similar pronouncements in the future.

The Rebbe gives several examples, continuing:

My experience with such people has convinced me that politicians are generally motivated more by expediency than by conviction. In other words, their public pronouncements on various issues do not stem from categorical principles or religious imperatives. Hence, most of them, if not all, are subject to change in their positions, depending on time, place, and other factors.

I believe, therefore, that the proper approach to such persons by Jewish leaders should not be rigid. As a rule, it does no good to engage in a cold war, which may often turn into a hot war; nor does it serve any useful purpose to brand one as an "enemy" or an "antisemite," however tempting it is to do so. It can only be counter-productive. On the contrary, ways and means should be found to persuade such a person to take a favorable stance, at least publicly. We haven't too many friends, and attaching labels, etc. will not gain us any.5

“Sure enough,” Professor Dershowitz continued, “shortly thereafter, Helms assumed a very influential role in the United States Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and before long, he became one of the strongest supporters of Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people, and of other Jewish causes as well”…

Politicians are generally motivated more by expediency than by conviction. In other words, their public pronouncements on various issues do not stem from categorical principles or religious imperatives.“[The Rebbe’s approach] had an enormous influence on persuading Jesse Helms that, even with his very conservative values, he could become a beacon for the Jewish State.” Indeed, many on the Christian right who had previously been venomous foes of Israel followed right behind him.6

Leaders and Alliances

Rabbi Yehoshua Kling was the rabbi of Lyon, France, for eight years, and thereafter, of Nice. In a meeting with the Rebbe in the mid-1970s, he sought advice for antisemitism that his community was facing.

The Rebbe explained that, in most cases, cues for antisemitism—whether by a political movement, or a certain population or demographic—come from the heads of a group, rather than the foot soldiers. It is one of those areas where the rank-and-file takes cues from their leaders.

The best way to proceed is to build connections with the leadership of these communities, and to utilize those relationships to influence them to work against antisemitism.For this reason, he explained, the best way to proceed is to build connections with the leadership of these communities, and to utilize those relationships to influence them to work against antisemitism, or at least to stop practicing it. Conversely, spending time with the “foot soldiers” to change their attitude is, for the most part, an inefficient deployment of resources.

Defuse the Issue

This leads us to a key aspect of the Rebbe’s response to antisemitism: In the cases we can find, the Rebbe responds to each situation by doing his best to defuse it, resisting the urge to call out an incident and give it oxygen. The Rebbe repeatedly seems to turn the discussion from the ugliness of a particular incident to a more global conversation; from highlighting a problem to investing in big-picture solutions.

Each and all descend from the one and the same single progenitor, a fully developed human being created in the image of G‑d.In late 1991, the Rebbe received a letter from the office of the President of Poland apologizing for an antisemitic incident in Warsaw. After expressing gratitude for the correspondence, the Rebbe continued:

You express the hope that in the future, intolerance and prejudice will disappear from the Polish people, and that you are working towards this end. We appreciate the sentiments expressed in your letter, and we pray that your hope and efforts will materialize very soon indeed…

Our Sages explain why the creation of man differed from the creation of other living species and why, among other things, man was created as a single individual, unlike other living creatures [which were] created in pairs. One of the reasons—our Sages declare--is that it was G‑d’s design that the human race, all humans everywhere and at all times, should know that each and all descend from the one and the same single progenitor, a fully developed human being created in the image of G‑d, so that no human being could claim superior ancestral origin; hence they would also find it easier to cultivate a real feeling of kinship in all inter-human relationships.

In the summer of that same year, a spasm of virulently anti-semitic riots, unfolded on the streets of Crown Heights, just outside the Rebbe’s windows. A black leader visited the Rebbe, expressing his solidarity. The Rebbe replied in terms similar to the above-mentioned letter:

…I hope that in the near future [New York’s] melting pot will be so active that it will be not necessary to underscore every time that these are “negro,” these are “white,” they are “Hispanic” etcetera, etcetera. Because they are not different. All of them are created by the same G‑d, for the same purpose: to add in all good things around them…

That summer, numerous police officials, leaders of organizations and politicians visited to express their horror and outrage. The Rebbe did not spend words on condemnations, labels, or blame—even rejecting suggestions for counter-demonstrations. Rather, he consistently turned the conversation to finding shared values, emphasizing what we share as members of the human race.

Healing the Cause, Not the Symptoms

Let’s return to the second cause of antisemitism explained above. How do we fill the void? How do we address the emptiness that gives rise to hatred of Jews?

Every human being, by their very nature, needs meaning; a sense of higher purpose. These individuals are part of the same civilization as us.

Well beyond the context of antisemitism, the Rebbe returned to this theme time and again: We’re not living on an island. Ultimately, it’s in everyone’s interest that the coinhabitors of society have direction and meaning in their lives, which can only begin in earnest from an understanding of the difference between right and wrong, and by living life in accordance with that understanding.

And in Torah’s view, the only true way for a human being to lead a life of goodness and kindness and of true tolerance for the “other,” is when it is based upon the knowledge of an Eye that Sees and Ear that Hears, a Director of this world, Who cares and pays full attention to every detail, every choice, and every action of your life.

This leads to many related areas that are beyond the scope of this article; topics that the Rebbe spoke about often and at length, such as education and universal values.

Education, in the Rebbe’s view, is the cornerstone to all of civilization. As he explained in his letter to Professor Dershowitz, the Rebbe passionately advocated that public schools in the United States devote a moment of silent contemplation to the beginning of every school day. The Rebbe’s very strong and specific opinion on the importance of a Moment of Silence in the US public school system was laid out in numerous talks and letters.

In a similar vein, the Rebbe spoke often and with great urgency on the importance of publicizing the Seven Universal Laws that G‑d gave for all of humanity such that individuals, and eventually society as a whole, will begin to live by Torah’s guidance for life. Here, too, the Rebbe argued that this is the only path for civilization to save itself from cannibalizing itself.

What’s more, it’s our duty. Torah teaches that we owe this to the society in which we live.

So you can’t fight antisemitism with a stick. We’ve got to help society find the “on” switch to turn on the light. It’s merely a “side” benefit, as Jews, that we’ll be helping to heal our gentile neighbors of the disease of antisemitism. Helping them to heal their emptiness is the only true way to ensure the next Haman won’t have a need to fill that ditch in his field.

Summary

Key directives we’ve garnered from these incidents and the Rebbe’s responses:

-

We need to realize that G‑d protects us and will continue to do so.

-

Do engage in practical security, the natural means through which we protect ourselves.

-

Exert your influence through quiet diplomacy, but don’t lose your backbone. Maintain pride in yourself as a Jew, and in your Jewish observance.

-

It’s not effective to confront someone by proving that he or she is an antisemite. On the contrary, where possible, do your best to engage them.

-

Concentrate on building relationships with leaders rather than chasing down the misdeeds of the followers.

-

Don’t spend your energy answering specific individual complaints against the Jews.

-

Emphasize how we’re all in the image of G‑d; the things that all human beings share.